During the recent National Council on Public History conference, I had the privilege of moderating a session on the subject of “Making the Invisible Past Visible.” This post will serve as a brief summary and list a few further resources.

The conference program described Session #S23 (Friday, Apr. 17, 8:30-10:00) as follows:

“Exploring a forgotten story of black freedom during the Civil War; ghost tours as a more diverse and inclusive public history; the built environment and what-might-have-been — studying unbuilt architectural proposals; cracking government secrecy through the Freedom of Information Act at the National Security Archive. What are the different ways history can be “invisible”? What is the political character of invisible history? What kinds of invisible history are in your community? What “traces” can aid in making invisible history visible?”

The session format was four speakers talking for about 10 minutes, followed by a brief period of cross-panel discussion, with the remainder of the time spent in small groups discussing audience members’ own thoughts about “invisible history” in their own communities.

Presenters included:

Linda Barnickel (myself), archivist and freelance writer

Glenn W. Gentry, Lecturer at Cortland University in New York

Christine Kreyling, freelance writer and architectural critic for the Nashville Scene

Nate Jones, director of the FOIA Project at the National Security Archive at George Washington University

Summary of presentations

Linda Barnickel

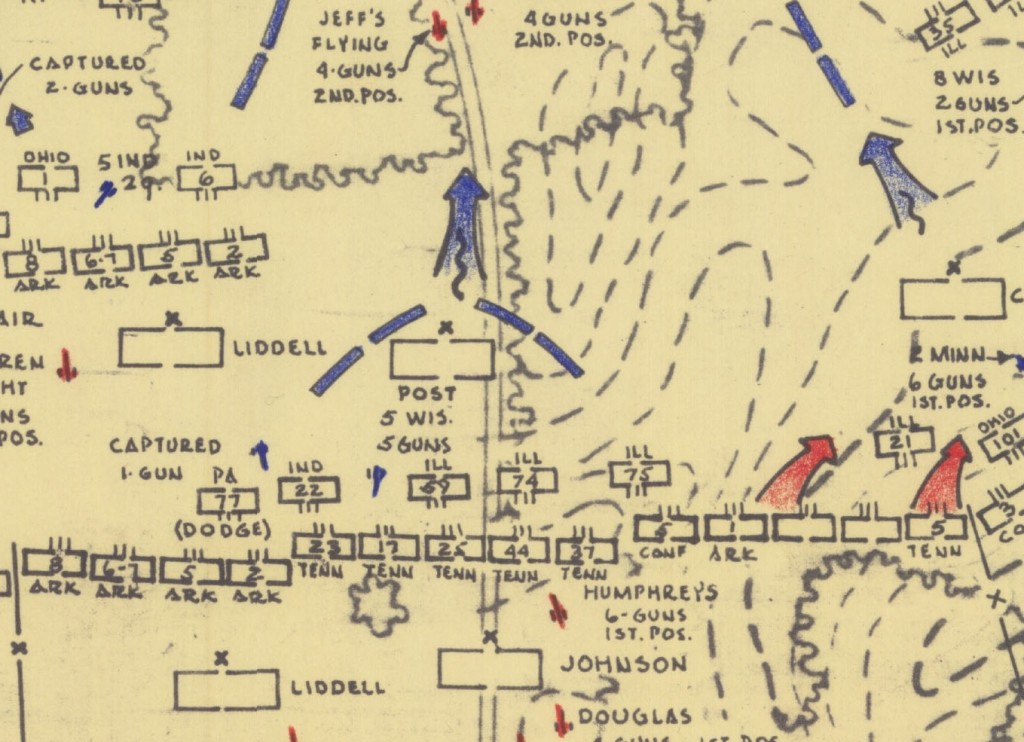

I spoke about my work researching the battle of Milliken’s Bend, a small and long-forgotten battle during the Civil War that nevertheless had significance in the larger narrative of African Americans serving in the Union army and their fight for freedom. Time did not permit me to speak in any detail about the history of the battle, and that information is now readily available elsewhere. Instead, I focused on the “invisibleness” of the story of Milliken’s Bend. I examined some of the reasons why it had been forgotten for so long, and outlined some of the methods I used for doing my research, including expanding my research beyond the finite boundaries of the battle at Milliken’s Bend on June 7, 1863 to include broader issues in place, time, culture and context.

For more on the historical story of Milliken’s Bend:

Milliken’s Bend website

Book: Milliken’s Bend: A Civil War Battle in History and Memory (LSU Press, 2013).

Follow Linda on Twitter at: @MillikensBend (for Civil War & related subjects)

or @LindaBarnickel (for general history, archives, writing, research, etc.)

Glenn W. Gentry

Gentry spoke about ghost tours. A geographer, not a historian, Gentry raised a number of thought-provoking points, explaining that ghost tours are often stories that a city “doesn’t want you to know” or that are whispered about in the shadows, hidden from the mainstream. Ghost tour guides often engage their audiences as participants (not tourists), and encourage them to tell their own stories, as well. Gentry spoke a lot about the story-telling and performative nature of ghost tours, including engaging the participants in the possible: “what may have happened; what is rumored to have happened; and what we (or they) don’t want to say happened.” He also pointed out that ghosts are far more about the present than they are about the past; in fact, ghosts only exist in the present. Ghost tours enable the public to engage with the past and the landscape in ways that they normally wouldn’t, and hear stories about people, places, and events that have often been left out of the usual narrative.

Additional resources:

“Walking with the Dead: The Place of Ghost Walk Tourism in Savannah, Georgia,” in Southeastern Geographer 47.2 (Nov. 2007)

Preview in ProjectMuse

Glenn W. Gentry and Derek H. Alderman, “A City Built Upon its Dead: The Intersection of Past and Present through Ghost Walk Tourism in Savannah, Georgia,” in South Carolina Review 47.2

Christine Kreyling

Kreyling spoke about “The Nashville We Didn’t Build,” exploring the value, impressions, and sometimes downright “kooky” proposals by architects and city planners that were envisioned and proposed, but never constructed. Based heavily upon research in private papers and newspapers, as well as surviving architectural plans, and using numerous illustrations, Kreyling examined these themes: the predominence of the “tall tower” concept; the way urban transportation, particularly the growth of automobile traffic, influenced urban planning; the tension between preservation and demolition; futuristic visions of monorails, moving sidewalks, and UFO-like appendages on buildings; urban renewal’s impact on the downtown core and its population; and wildly varying scenarios for repurposing the Union Station Train Shed, which was eventually demolished in 2001, despite its National Historic Landmark status.

Additional resources:

“The Nashville We Didn’t Build,” Nashville Scene, July 10, 2003.

[online article is minus illustrations that appeared in the original print version]

Book: The Plan of Nashville: Avenues to a Great City (Vanderbilt Univ. Press, 2005)

[A 50-year vision for the future of the city]

More Books by Christine Kreyling

Nate Jones

Jones provided a whirlwind tour of the work of the National Security Archive (NSA) – an independent, non-govermental institute housed on the campus of George Washington University. The NSA works to uncover government secrecy using the Freedom of Information Act, known as FOIA (pronounced “FOY-yuh”). Among his examples: a tripartite comparison of a Wikileaked document, the initial release of the same document from the State Department under FOIA, and the final release from the State Department after a FOIA Appeal. Jones also spoke about the Able Archer nuclear war scare in 1983, which he has researched extensively. Other intriguing documents shown: fingerprints of Sadam Hussein and an FBI document containing statements Hussein made while in U.S. custody; a history of American cryptology during the Cold War; a mention-in-passing of several Civil Rights leaders on a 1960s FBI watch list of “domestic terrorists and foreign radical suspects,” including Martin Luther King, Whitney Young, and Muhammed Ali; and at last – government confirmation that Area 51 does indeed exist in the Mojave Desert!

Additional resources:

Unredacted – the National Security Archives’ blog, many posts written by Nate Jones

FOIA resources from the National Security Archive

Effective FOIA Requesting for Everyone guide

Follow Nate Jones on Twitter: @NSANate or the National Security Archive at: @NSArchive

Other Resources about NCPH2015:

View a Twitter feed about this entire session.

Various post-conference resources, links, and compilations.