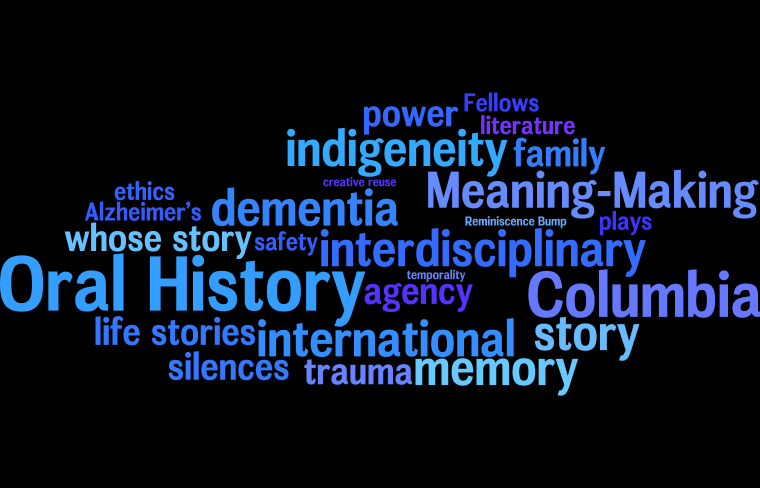

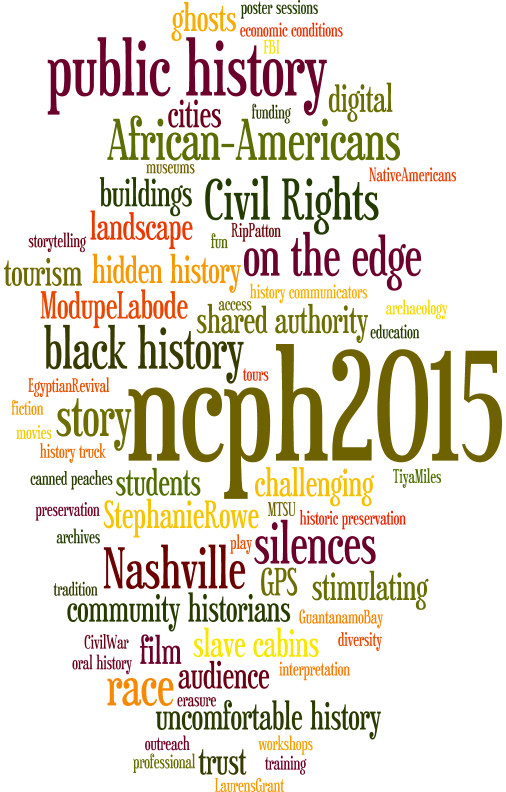

I’ve accumulated quite a number of books that I need to read or review in the wake of the summer 2017 Columbia Oral History Institute. It will probably keep me occupied till the end of the year. Even before the institute, I was thinking quite a bit about interdisciplinarity, and how that relates to oral history, public history, and aging. The concept of interdisciplinarity was only further reinforced during the institute. I think this list reflects that.

A few of the titles appearing below I have read, but many of them I have not. So these are not necessarily recommendations as much as they are simply a “to read” list. Outside of the thematic groupings, there is no order to the list.

Please feel free to add more suggestions or comment on any of the books that you have read in the “Comments” field at the end of this post.

Note: Links to Amazon appear through their Affiliate Program, in which I receive a few cents from any purchases made through the Amazon website. Links here are provided primarily for convenience, as a way to read reviews, view table of contents and use many of the other functions available through Amazon. Some publications are out of print; these links are directed to Worldcat, where you can see if your local or nearby library has a copy.

Historiography & Memory

Robert Eric Frykenberg. History and Belief: The Foundations of Historical Understanding. (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1996).

Joan Tumblety, ed. Memory and History: Understanding Memory as Source and Subject. (London: Routledge, 2013).

Charles Fernyhough. Pieces of Light: How the New Science of Memory Illuminates the Stories We Tell about Our Pasts. (NY: Harper Collins, 2012).

Writing and Memoir

Stephen J. Lepore and Joshua M. Smyth. The Writing Cure: How Expressive Writing Promotes Health and Emotional Well-Being. (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2002).

Mary Karr. The Art of Memoir. (NY: Harper Perennial, 2015).

Rebecca Solnit. The Far Away Nearby. (NY: Penguin, 2013).

Rebecca Solnit. A Field Guide to Getting Lost. (NY: Viking, 2005).

Louise DeSalvo. Writing as a Way of Healing: How Telling Our Stories Transforms Our Lives. (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999).

Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson. Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives. 2nd ed. (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2010).

Sven Birkerts. The Art of Time in Memoir: Then, Again. (St. Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2008). [and probably other titles in the Art Of series ed. by Charles Baxter.]

Literature, Literary Theory, and Narrative

H. Porter Abbott. The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative. 2d ed. (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

Daniel Taylor. The Healing Power of Stories: Creating Yourself through the Stories of Your Life. (NY: Doubleday, 1996). Republished in paperback as: Tell Me A Story (Bog Walk Press, 2001).

Arthur W. Frank. Letting Stories Breathe: A Socio-Narratology. (Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press, 2010). This is by the author of

Richard Stone. The Healing Art of Storytelling: A Sacred Journey of Personal Discovery. (NY: Hyperion, 1996).

Seymour Chatman. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. (Cornell Univ. Press, 1980).

Jean Aitchison. Words in the Mind: An Introduction to the Mental Lexicon. 4th ed. (West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012).

T. S. Eliot Four Quartets. (Various publishers)

William Faulkner. Absalom, Absalom. (Various publishers)

Veterans, War, PTSD, and Trauma

Edward Tick. War and the Soul: Healing Our Nation’s Veterans from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. (Wheaton, IL: Quest Books, 2005).

Patience H.C. Mason. Recovering from the War: A Guide for All Veterans, Family Members, Friends and Therapists. (High Springs, Fla.: Patience Press, 1998). Now rather dated, but still useful content, with many excerpts of an oral history nature from Vietnam veterans.

Tian Dayton. Trauma and Addiction: Ending the Cycle of Pain through Emotional Literacy. (Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications, Inc., 2000).

Jonathan Shay. Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character. (NY: Scribner, 2003).

Jonathan Shay. Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming. (NY: Scribner, 2002).

Tim O’Brien. The Things They Carried. (Various publishers.) A work of fiction, but relevant for insights about narrative, memory, and trauma. See particularly the chapter, “How to Tell a True War Story.”

Barbara Sommer. Doing Veterans Oral History. (Oral History Association, 2015).

Donald H. Whitfield, ed. Standing Down: From Warrior to Civilian. (Chicago: Great Books Foundation, 2013).

Cathy Caruth. Listening to Trauma: Conversations with Leaders in the Theory and Treatment of Catastrophic Experience. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2014).

Victor Frankl. Man’s Search for Meaning. (Various publishers).

J. Martin Daughtry. Listening to War: Sound, Trauma, Music and Survival in Wartime Iraq. (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Family History and Family Stories

Karen Branan. The Family Tree: A Lynching in Georgia, A Legacy of Secrets, and My Search for the Truth. (NY: Atria Books, 2016).

Thulani Davis. My Confederate Kinfolk: A Twenty-first Century Freedwoman Discovers Her Roots. (NY: Basic Books, 2006).

James Carl Nelson. The Remains of Company D: A Story of the Great War. (NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2009).

Still to come:

Reading List on Alzheimer’s, Dementia, and Caregiving